Renowned naturalist Waldo Lee McAtee recorded the presence of numerous magnolia bogs in the Washington, DC area during the early part of the 1900’s. Among the ones he cataloged in A sketch of the natural history of the District of Columbia – 1918 was a bog in Odenton, the exact location of which is not clear. He described this bog as “one of the best developed magnolia bogs in the region” that was “somewhat cut up by railway embankments.” He also noted that it was near a “sandy locality of considerable interest to collectors.” In the late summer, orange milkwort (Polygala lutea) and white-fringed orchid (Platanthera blephariglottis) in the bog is said to make a “gorgeous show.” Bear oak (Quercus ilicifolia) and pitch pine (Pinus rigida) were also sighted in the area. McAtee also noted that the floristic composition of the Suitland Bog and the Odenton Bog is similar to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey (McAtee, 1918).

With this information in hand, it might be possible to rediscover the Odenton Magnolia Bog. There is a candidate area on the Patuxent Research Refuge which deserves consideration, and that is the putative magnolia bog that is located just south of the Clean Fill Dump (CFD) on the eastern edge of the Refuge’s North Tract. There are at least three references of this so-called magnolia bog in documents describing the CFD. (Environmental Protection Agency, 2000; URS Group, Inc., 2011; Fish and Wildlife Service, 2013).

The author has not yet been able to find a direct historical connection between the magnolia bog described by McAtee and the one south of the CFD. However, the descriptions of the bogs provides a possible clue. McAtee referred to the bog being “cut up by railway embankments.” The eastern edge of the CFD bog is about 500 to 600 feet from the Penn Line. This means that McAtee’s Odenton bog and the CFD bog could be the same site. A closer examination of the site and the discovery of historical references may resolve this question.

Preliminary surveys of the CFD site in March 2015 revealed that the site was indeed boggy in character. There was a fairly dense understory and there were scattered medium-sized patches of sphagnum moss as well as sphagnum moss covered hummocks scattered throughout the area. The muck in the middle of the bog was up to 2 to 3 feet deep. The area was on a slope of 5 degrees or less and was laced with indeterminate channels of running water. There is evidence that there is an upward vertical hydraulic gradient. Towards the CFD and along the western side of the boggy area, the water seemed to almost spontaneously percolate through the leaf litter. This was also noted in the assessments of the CFD done by the Army and the EPA. There is an elevated area with an upland forest to the northwest of the boggy area which is probably the source of water.

Soil composed of rounded gravel and cobblestone sized rocks and sandy silt was exposed in a few places on the road which bordered the CFD on the northern side and situated upslope from the CFD. This type of soil might be present in the boggy area to the south, or it could simply be fill dirt brought in from another location.

Overall, the habitats generally seem to transition from a magnolia type bog on the north near the CFD to a more swampy type habitat on the south. There was a sizable area with Phragmites towards the south. The water runoff continues south until it empties into the Little Patuxent River just east of Bailey Bridge Swamp.

An attempt to estimate the concentration of sweet bay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana) in the area was made. However, it has not yet leafed out. So an examination of the leaf litter was made to make a crude estimate. In some areas, there was little evidence of sweet bay magnolia leaves. While in others, there was a high concentration of magnolia leaves. A better estimate will have to wait until later. American holly (Ilex opaca) was scattered throughout, especially in the drier areas. Green brier (Smilax rotundifolia) seemed to be omnipresent. Pitch pine and Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) as well as other upland forest tree species were present. At least one pitch pine observed from a distance had black-colored bark. This indicates the possibility of a recent fire. Skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) in full bloom was poking up throughout the site. Red maple (Acer rubrum) was just starting to bloom.

The CFD is about 13 acres in area according to EPA assessment done for the Record of Decision (Environmental Protection Agency, 2000). The total extent of the historic bog is unknown, so it may be difficult to determine how much of the debris and soil from the CFD actually covers the original magnolia bog.

Looking at the micro-topography of the site as well as the direction of the water flowing into the bog, at least some of the toe slope seepages seem to have been located on the western side of the CFD. Based on what the author understands what a toe slope seepage to be, it is possible that the CFD debris has buried much of these seeps. There is some evidence of toe slope seepages around the margins of the CFD, and it is hoped that the author may have simply missed locating them. Expert confirmation of what is going on with the toe slope seepages is indicated.

A cursory examination of the bog on the southern margin of the CFD showed no visible contamination or siltation. Obviously, the author did not have the means to chemically test the water. Perhaps the Army and EPA assessments could be helpful to determine the level of chemical contamination.

A confirmation of exactly what type of habitat this is needs to be done. A floristic survey is scheduled for the 2015 plant season. Additionally, research to find more historical background of the bog and the CFD will be undertaken.

If the Clean Fill Dump bog is the same one that McAtee noted in 1918 (McAtee 1918) as situated in Odenton, why has it evaded the scrutiny of bog enthusiasts until now? The answer to this question is simple. It stems from the fact that the land upon which it is situated was part of the original Camp Meade that was established in June 1917 (http://www.ftmeade.army.mil/museum/Meade_Intro.html). This would essentially restrict access to scientists. I am not sure who actually “re-discovered” this site, but since it was called a magnolia bog in the documents assessing the clean-fill dump someone knew about it at least after the land was transferred to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The assessments of the clean fill dump do not adequately describe the site, and I have not yet been able to find any recent significant research done on the site.

CITATIONS

Department of Army. About Fort Meade, Fort Meade Museum On-line. http://www.ftmeade.army.mil/museum/Meade_Intro.html Accessed 10 April 2015.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Record of Decision, Clean Fill Dump (CFD), Operable Unit – 07, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland.

Fish and Wildlife and Wildlife. 2013. Patuxent Research Refuge, Comprehensive Conservation Plan.

Harrison, J.W., W.M. Knapp. 2010. Ecological classification of groundwater-fed wetlands of the Maryland Coastal Plain. Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Natural Heritage Program, Annapolis, MD. June 2010. 98 pp.

Hitchcock, A.S., Standley, P.C. Flora of the District of Columbia and Vicinity. Vol. 21. 1919.

McAtee, W. L. 1918. A sketch of the natural history of the District of Columbia. Washington, DC: Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washington

Simmons, R., Strong, M. 2001. Araby bog flora surveys. Maryland Native Plant Society, SAMMS.

Simmons, R., Strong, M. 2002. Fall Line Magnolia Bogs of the Mid-Atlantic Region. Audubon Naturalist.

URS Group, Inc. 2011. Draft Final, Second Five-Year Review Report, Clean Fill Dump Operable Unit, Patuxent Research Refuge – North Tract, Anne Arundel County, MD.

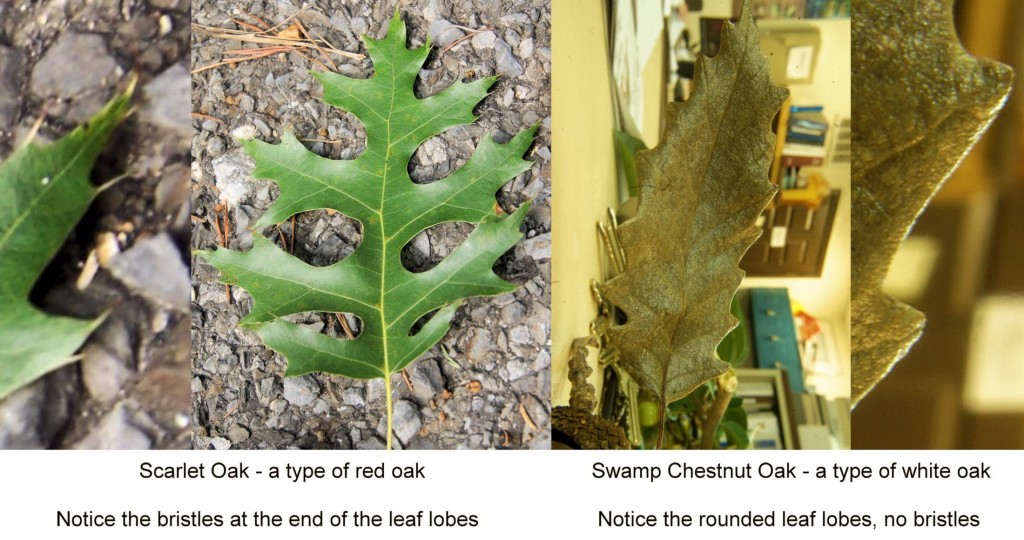

The oak-rich Patuxent Research Refuge has 16 native oak species, one naturalized exotic oak species, and at least ten types of trees that are regarded as oak hybrids. The reason so many oaks species call the Refuge their home is due to the Refuge location near the Fall Line between the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont and at the same time, it is at a crossroads between northern and southern species of oak.

The oak-rich Patuxent Research Refuge has 16 native oak species, one naturalized exotic oak species, and at least ten types of trees that are regarded as oak hybrids. The reason so many oaks species call the Refuge their home is due to the Refuge location near the Fall Line between the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont and at the same time, it is at a crossroads between northern and southern species of oak.